Robotic arms, 3D printers, wind turbines. These are the types of dynamic products senior engineering students typically pour their time into designing for their year-long group capstone projects, which are meant to demonstrate their mastery of the concepts they’ve learned over the course of their four-year degree program.

But this year, one TCNJ team wanted to take their skills even further — like, all the way to space.

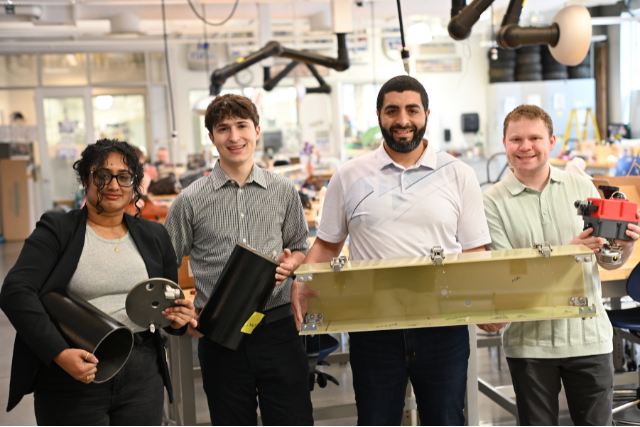

So a four-person team of mechanical engineering seniors set out to design equipment that would have real-life applications in space exploration. Co-captains Vaishnavi Adusumilli and Mohamed Eladawy, along with Kyle Luis and Pierce Rubenstein, took on NASA’s Human Lander Challenge Competition as their project. Now in its second year, the Human Lander Challenge tasks college students to find innovative solutions to the problems NASA’s engineers are grappling with as they prepare to send astronauts to the Moon (and eventually Mars) through the Artemis campaign.

The team’s “Cryogenic Orbital Siphoning System” or CROSS for short, is now one of just 12 projects nationwide — including those from MIT, CalTech, and Embry Riddle Aeronautical University — to advance to the next stage of the competition, to be held this June in Huntsville, Alabama.

This year’s competition asked each team to design rocket fuel storage and transfer solutions for large amounts of the super-cold liquid propellants that will be necessary for astronauts to spend more time — and bring more equipment — beyond Earth’s orbit than ever before. Current technology allows NASA to store these cryogenic fuels in zero gravity for several hours, but they need the capacity to store them for up to several months.

Prior to building their CROSS, the team admits they were initially intimidated by having to master a subject they knew nothing about.

“We’ve put in almost a thousand hours each. I’ve never had my brain fried before,” says Luis.

“The teams they are up against, some have students who already have postdocs and PhDs,” says team advisor Mohammed Alabsi, associate professor of mechanical engineering. “It’s a totally different story for a group of undergrad students who have done everything from A to Z, from conducting a literature review, to understanding the problem, proposing a solution, writing a proposal, and now making it to finals. They’ve done a phenomenal job.”

What they came up with, their CROSS, is a positive expulsion system that converts a portion of liquid rocket fuel into gas which drives a piston to push the fuel from the storage tank into its destination vessel. Its ingenuity lies in its simplicity, with the design requiring almost no electrical components, and the piston doing double duty as a scavenger, scraping any extra fuel that may stick to the sidewalls in zero-gravity.

“It’s a dream for all of us to be recognized, especially from The College of New Jersey, which is not necessarily known for aerospace engineering,” says Rubenstein. “It shows how much we’ve learned and how much we really understand what we’re doing — and also goes to show that all the work that we did really paid off.”

— Jessie Findlay